Virtue-licensed extraction comes to ChatGPT, for your own good, of course

Ads aren’t a betrayal, we’re told. They’re an ethical necessity. ChatGPT’s move into advertising isn’t about survival so much as the familiar ritual of monetising trust, wrapped in promises about restraint, responsibility, and values.

So ChatGPT is getting adverts. Not because it wants to, you understand, but because it has to. For sustainability. For access. To keep it free for you. For the greater good.

Its owners promise us three things, delivered with fitting solemn sincerity:

· Your data won’t be sold.

· Ads won’t influence what ChatGPT says.

· This is all perfectly compatible with trust.

That’s pretty impressive, because every platform that ever broke faith with its users started with exactly those sentences.

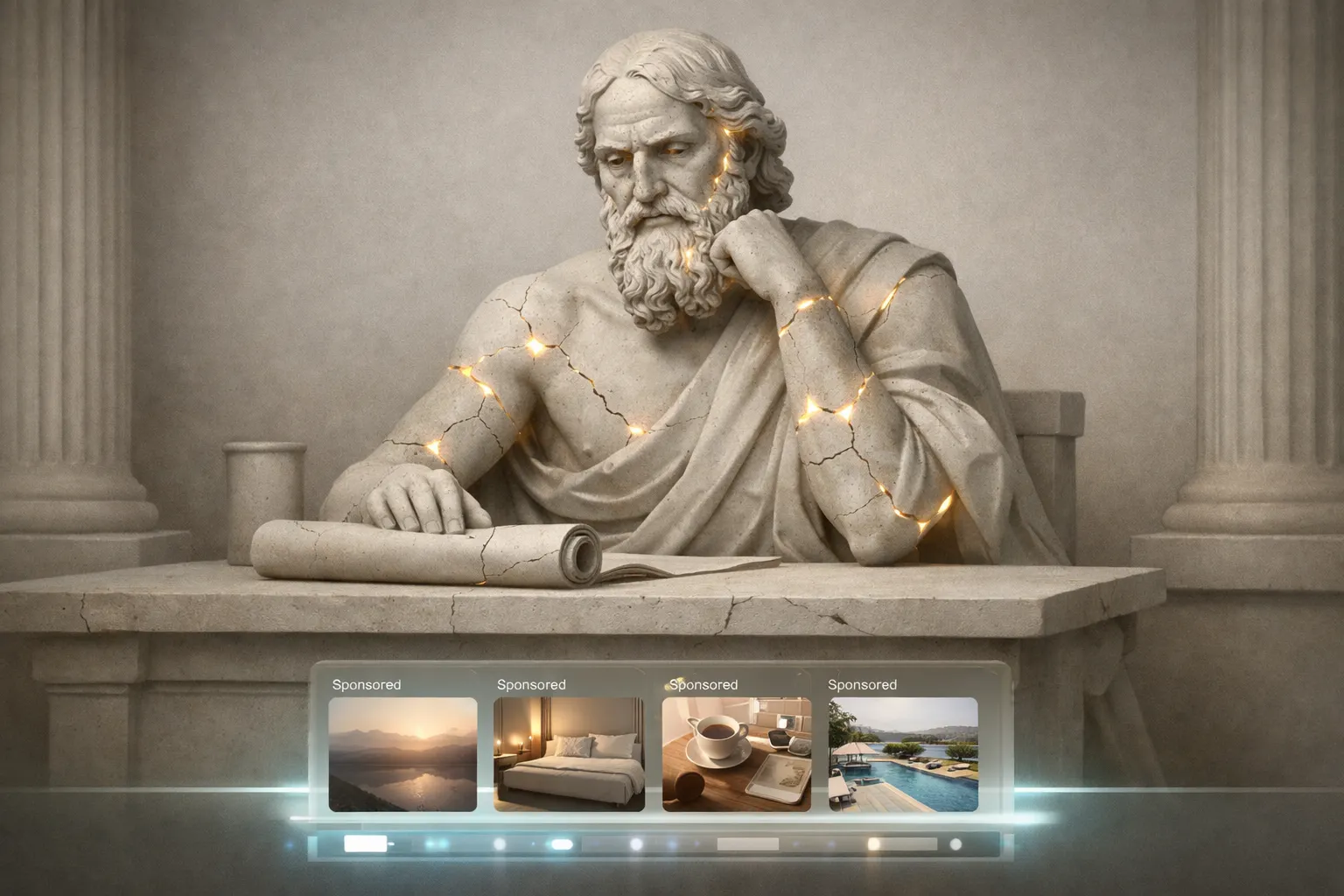

One word already doing too much work is “enshittification”; an ugly expression that sounds like a Silicon Valley intern trying to sound all grown up by swearing. What’s actually happening here, however, is virtue-licensed extraction: the slow monetisation of trust, justified in advance as ethical necessity.

First comes the pledge. Then the reassurance. Then the interface change that somehow wasn’t covered by the pledge.

Ads will be “based on what people ask”. But don’t worry, ChatGPT [or insert name of any bottom-feeding tech operation] won’t influence answers. They’ll just sit nearby. Quietly. Observing. Suggesting. Nudging. Entirely without consequence. Like cigarette smoke in a restaurant.

Naturally, no data will be sold. No, really. It never is. It’s merely used. Processed. Abstracted. Inferred. Fed into systems that mysteriously know what to place at the bottom of your screen at exactly the right moment. And then, just as mysteriously, they pop up on other devices you own.

Profit, of course, is never defended as profit. It’s defended as a responsibility. Monetisation becomes stewardship. Advertising becomes access. And questioning any of this is framed as naïve, because “these systems are expensive, you know”.

As a kid in church, I noticed the sermon always came before the collection plate. Maybe that’s where they learned the technique of appealing to a higher purpose before grabbing some cash.

Free users will see ads. Paid users won’t. Well, for now. That sentence has a very short half-life in the modern tech economy, as anyone with paid streaming subscriptions and ads before the opening credits will tell you.

We’re told the ads won’t influence what ChatGPT says. But influence isn’t binary. It lives in defaults, emphasis, placement, omission, and the slow reshaping of what counts as “helpful”. You don’t have to corrupt the oracle if you can quietly rearrange the temple around it.

Once again, we’re invited to trust the same way we always are: by being calm, reasonable, and grateful while the terms of the relationship are rewritten underneath us, with a “we are changing our terms and conditions” email. No consultation. Or consideration for that matter. Nowhere else in most modern legal systems does one side get to set all the conditions.

At the end of the day, we are no longer users. We are not even customers. We are moral collateral — the trust being drawn down, one ethically-justified adjustment at a time.

This isn’t a scandal. It’s a business model doing exactly what it was always going to do.

And the reassuring part? They promise they won’t go too far.